Lear in Greece 1856

In August 1856 Lear set out from Corfu to visit Mount Athos, a journey that would take him right across the mainland and then via Salonica to the peninsula of Chalkhidikí. Notable sights on the way were the town of Ioannina and the Meteora monasteries. Click here for a map of Lear’s route.

This webpage includes Lear’s written account of the journey from Corfu as far as Salonica, together with a selection of his drawings. His lists suggest that this portion of the journey yielded about 30 landscape sketches made on the spot, and one studio watercolour and one oil, painted later. I have traced nine of the sketches.

The text is based on letters to his sister Ann, which survive in transcribed copies (my Editor’s Note gives further details), and an excerpt from a letter to his friend Chichester Fortescue, published in Letters of Edward Lear (1907).

The tour of Mount Athos itself has been separately edited by Stephen Duckworth: see the site Drawings and other pictures of Mount Athos by Edward Lear.

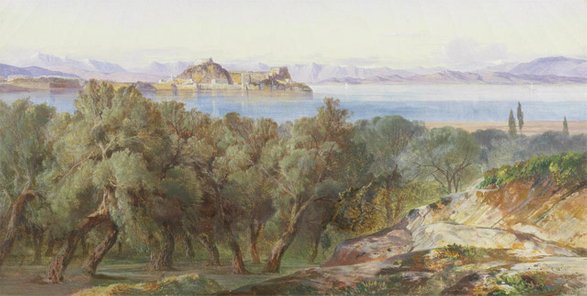

View of Corfu, oil, 1856.

Private collection.

A favourite view of Lear’s, towards the town and the Citadel. In the distance are the Albanian mountains, offering a contrast to the softer, more domesticated landscape of Corfu.

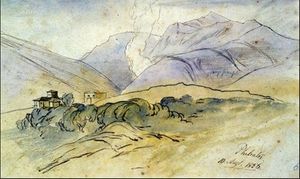

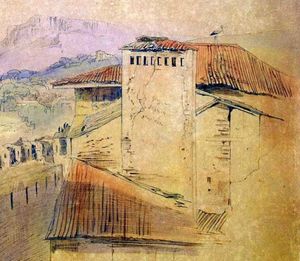

Delvino, 9 August 1856

and 20 April 1857.

St Cross College, University of Oxford.

Lear visited Delvino three times. As the two dates on this watercolour indicate, he began sketching the Turkish fort at the beginning of the Athos trip, and worked on it again the year after.

Philates, 10 August 1856.

Gennadius Library, Athens.

Philates was an important settlement of about 2,000 houses a dozen miles inland. In 1849 had Lear regretted not having time to stop to draw “a place bounding in exquisite beauty”.

Click on any image to enlarge.

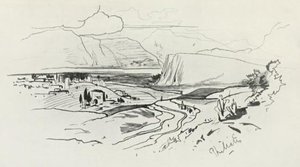

Philates.

Pen and ink sketch, from a letter.

Philates, 13 August 1856.

Tate London © 2018.

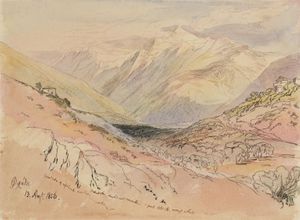

Philates, 11 August 1856.

William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow,

London Borough of Waltham Forest.

A prominent feature of the landscape was a distinctive rock formation, visible from Corfu: “I long to land there once more, & to draw the great rock of Philates”.

Philates: the house of Jaffier Pasha (detail),

11, 12, 13 August 1856.

Gennadius Library, Athens.

Lear made at least ten drawings of the “house”, a walled and fortified conglomeration of buildings affording much avian and human interest. Years later he “Looked again vainly for the dear old drawing of Philates Castle, with all the Albanian Beys sitting”.

Philates: the house of Jaffier Pasha.

Ottoman-era houses sometimes had a staircase with irregular rises to confuse and repel invaders. This sketch, made by Lear from memory many years later, perhaps depicts the stairs responsible for his serious accident on 10 April. (Lear reported he fell down 19 stairs.)

The landscape near Philates (Filiates) today.

During the Ottoman period Salonica was a cosmopolitan and multiethnic city with a sizeable Black population; this young woman may have worked in the hotel where he was staying. Lear’s sister Ann was always interested to hear details of the women’s clothes he saw on his travels. This study is faintly numbered 16 (lower right).

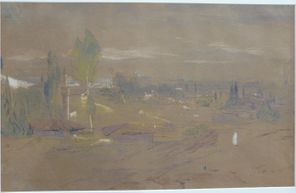

On his way back to Corfu after visiting Athos Lear drew Salonica from the Byzantine Monastery of Vlatadon; Mount Olympus can be seen in the far distance. His colour notes record “yellow thistles on bare dry gray earth”.

A Seated Greek at Philates,

10-14 August 1856.

Guy Peppiatt Fine Art.

During his enforced stay at Philates because of his injured back, Lear turned to sketching subjects near at hand. The distinctive red fez and sash often feature in his Balkan landscapes, adding a dash of brighter colour to the predominantly green, grey and brown tones. This study is numbered 10 (lower right) in his 1856 series of at least 16 figure sketches.

A Greek Man at Philates,

10-14 August 1856.

Guy Peppiatt Fine Art.

Despite studying for a year at the Royal Academy Schools in 1850 (when he was already in his late 30s), Lear was conscious of a lack of formal training and was never confident drawing the human figure. Nevertheless, small figures are an important element in his landscapes, and he sometimes made separate studies of people in local costume. This standing figure is numbered 13 (bottom right).

Nubian Girl, Salonica, August 1856.

Lyon & Turnbull Auctioneers.

From the “arrangement of the hills, and the disposition of the foregrounds”, Lear judged the landscapes near Philates “some of the very finest scenes in all Albania and its environs”.

Salonica, 23 September 1856, 5pm.

Gennadius Library, Athens.

Lear’s account of his 1856 journey

13th August 1856, Philates, opposite Corfû

—Here is a novelty for you!! When I came to town I went to stay a day or 2 with Frank L. till my rooms could be cleared properly. And, as my big canvasses had not come, I made up my mind to see a little bit more of the world before working hard again. F. Lushington & Col. & Mrs Ormsby [1] were to go on the 7th to Délvino—so I agreed to join them, as I had never seen that part of Albania—& then, I planned to go to Janina, & if possible on to the long desired Mount Athos,—so as to return to Corfu as early as possible in Sept. Now you are to be clear that in these days things are not as they were in 1848: we now have consuls at many places, & although I take a bed & cooking things—yet I shall want them but little. Our yacht trip over to Sta. Quarantina was delightful—-& for once I am beginning to like yachts—at least, the little Midge. On the 8th the Ormsbys, Frank & I, went early to Délvino—which is immensely picturesque; it seemed odd enough to come all at once again into the use of divans & round tables & cross legs! But the wonderful picturesqueness of Albania is as new & beautiful as ever—& after the eternal, though lovely olives of Corfu—I must say we, F. & I—found it very refreshing.

On the 9th we returned to the coast, & there Col. & Mrs O. left us, & we 2 ran down in the Midge to Scala Saiada where early on the 10th we landed, taking also my man Giorgio & my luggage. We were soon at this place [Philátes], & well lodged in the house of Jaffier Pasha [2]—& how I wish you could see it! It is one of those strange all roof & lattice Turk houses, enclosed in a court with high walls & towers; the walls are black with jackdaws, & the towers white with storks who clatter as of old. I am sorry to tell you that in the afternoon I had a baddish fall—down a flight of stone stairs; the matter might have been serious, but happily I broke no bones,—though I did not feel able to move for travelling until after a good rest. So I have stayed here through the 11th–12th &13th—& tomorrow I shall go as far as Keramítza on my way to Janina, but if I find the least chance of my being unwell—shall return to Corfû at once—which I can see from the hills close by. My going on to Athos depends on that & also on what I may hear when I get to Sigr. Damaschino’s, our Consul at Janina, where I shall also find Mr Saunders [3]. I certainly should like to see the wonderful & beautiful Athos—& this is the 3rd time of trying. [ . . . ]

I am much better today—indeed well—and the journey is only of 5 hours tomorrow, to begin with. I find all the difference in the world here from being able to speak—(even as little as I do)—in Greek. Giorgio speaks Albanian also, so we do very well. I find him an excellent, active, and quiet servant, thus far. [. . . ]

I will get you some embroidery, or somewhat, from Janina. Meanwhile I will write to you from there, and from Lárissa, and Salonika—if I ever go there—so you will know all my doings regularly enough.

August 21st 1856, Larissa

My dear Ann,

I shall begin a letter to you here, hoping to send it to you from Saloniki, where I trust to be in a few days. So far my journey has been very prosperous, but as I sit in a beautiful room at the English Consul’s house here, with sofas all round the walls, matting on the floor, & painted ceilings, & look out on a little court yard where 2 tame cranes are walking up & down—I cannot but think how much easier it is to travel in these parts now than it was in 1848. Moreover, I believe the race of dogs which used to rush & rage & bark are civilised & changed also—or dead—the result being the same, that I have not been bothered by them at all. I sent you a little letter on the 13th from Philátes,—so I knew you would like to know how I was getting on, & that you would like a short note better than none.

On the 14th I started for Janina,—Col. Ormsby not having come,—with Giorgio alone: unluckily we had a bad muleteer who would not stop when he was told, & who put us to great inconvenience. He would not go the direct road to Janina—for some reasons of his own, so we were far off at sunset—but as he was crossing a river—(& we found afterwards that he did so to avoid the Bridge toll [4] for his horses)—some Guards seized on us all in a bunch—& a pretty fuss there was! My passport &letters were enough to ensure me being taken on to the next village—but our muleman was tied & taken off,—very properly—to be punished. Next day 15th we got to Janina, & here I had a comfortable rest in Mr Damaschino’s house, our Consul. There has been a great fire lately at Janina,—but it has not injured the general outline of the city, & I think that the scene of the Citadel, Lake & mountains, is really one of the grandest & most beautiful I ever saw; so much so that I believe I shall make it the subject of one of my large canvasses during next winter. From Janina, we came by the Mézzovo Pass road—Malakássi,—the Metéora Monastery, &Trícala to this place, where I arrived last night. Certainly the wet days of Thessaly in 1849 are not repeated now!—there is no colour in sky & earth but blue, pink, & bright yellow—the latter being all the plains—now stubble. I thought as I entered last night, that Olympus & Ossa seemed as if made of rose colour & lilac velvet, the bright white minarets of Lárissa like tall silver or diamond lights—& all the earth, as the sun set pure orange gold. I set off today on my pilgrimage to the Holy Mountain (which I hope to see afar off tomorrow) & sleep at Tempe—going on to Platamóna etc. When we were coming down the plain of the Salympria [Pinaeus], near Trícala— what do you think we met? Why, 2,500 mules!—all carrying corn. I never saw so many mules in my life—all going one by one—& I thought the world was gradually turning wholly into mules. Meeting them when we did, was a piece of great good fortune,—for on the Mézzovo Pass there are many points where only one beast can pass at a time, & you have to wait to meet in a wider place: but as 2,500 mules could not go back for 2 or 3, there would have been no choice but to return to the next Khan, & wait a day or more till the Mule-stream had subsided.

Aug. 26th, 1856, Saloniki

Just 8 years ago since I came to Salonica from Constantinople! & here I am in the very same room, & everything seems pretty much as it was, save that the black landlady [5] is dead, & people are all 8 years older. Well—I should have been here 2 days ago,& very provoking it is to lose such lovely weather,— for in Sept. rain must come some time or other. I could not get away from Lárissa before the afternoon of the 21st—intending to sleep at Babá, that lovely place on the river at the entrance of Tempe; but it grew dark, & we had to stop at a village 2 hours earlier. The inhabitants of that village are descendants of people of Konya in Asia Minor, whom some Sultan brought in a lump from their own country, & stuck down here in Thessaly.[6] They keep their own dress & customs to this day, & look queer enough among their neighbours. However, one, [?] Mahmud, lent us a square empty house, which would have been extremely nice, only so many cats run about continually. Giorgio soon made a fire, with some tea & cutlets—so one didn’t fare badly. He is the best of all servants I have had abroad, because, besides his capability as interpreter & cook, & general travelling domestic, he is so good a house servant & has always been used to the duties of valet to Englishmen at Corfû: moreover, he is never out of temper at all, though the life of a journey is always more or less a trying one. On the 22nd I passed the wonderfully beautiful Tempe—on foot—for it is a shame to go through it quickly. I thought the Plane trees bigger, &the river clearer than ever. Then came the famous vale of Tempe—(which, if you remember, I had not seen in 1849—because I turned back again to Lárissa). And most lovely it is—green as far as you can see with immense Plane, Abele, & Oak trees, & with Mt Ossa above & the sea beyond. But I made no drawings,—having in view Mt Athos particularly, & laying down a rule that nothing was to prevent my getting there in preference to all other matters. We passed Platamóna in the day & got to S. Teodoro Khan at nightfall.

23rd We were at Katerína till midday, & then, worse luck!—went down to the sea shore, to take a boat across to this place—only 2 hours off by sea, & 16 by land. But lo! no boats were to be found! All had started to bring over 300 families from here, to a great fête at some monastery—nor could a single horse be found, & our muleteer returned next day—24th—in spite of all offers. So there we were; & a great wind rising, no boat could cross. And we ate up the last bit of our meat—for the Khan had nothing but coarse bread & a little rhum—& when no boat came on the 25th morning, we began to speculate how Giorgio should cook the large blue jelly fish that the sea threw up. We found 2 small crabs also—& I proposed—as there were blackberries all about, to boil the jelly fish with blackberry sauce, & roast the crabs with rhum & bread crumbs—a triumph of cookery not reserved for us—for at last boats began to come, & horses appeared over the hills by scores. The boats however would not return & it was with great difficulty that we could induce 3 horses to move. Very good ones they were however, & setting off at 9 we came to Salonica by 6 o’clock—& thus far my Mt Athos trip is accomplished.

I found Mr Blunt, our Consul [7], & oddly enough they all recollected me as being there in 1848. He gives me letters to the monks of Athos—&I dine with the Blunts today, & set out early tomorrow—a day of repose (comparative) is never thrown away. The inconvenience resulting from my fall diminishes daily, & otherwise my health has greatly improved by this journey; that is, I feel stronger & better than when I set out. [ . . . ]

And now I will tell you in a few words, somewhat about Mt Athos, where I am going.

[The journey continues in Stephen Duckworth's edition: see Drawings and other pictures of Mount Athos by Edward Lear.]

A brief summary of the 1856 journey in a letter of Lear to Chichester Fortescue:

Quarantine Island, Corfu, 9. October, 1856.

“. . . off I set on Aug. 7th taking my servant, canteen, bed & lots of paper & Quinine Pills. F. Lushington saw me as far as Φιλάτες, but then I fell down a high flight of (19) stone stairs & damaged my back sadly. I thought I was lame for life, but after 4 days on a mattress, I got on pillows & a horse, & went over to Yannina & to Pindus, & (in great pain) to Larissa, & finally to Saloniki.”

NOTES

[1] Franklin Lushington, lawyer and classical scholar, had toured Greece with Lear in 1849. In 1855 he was appointed judge to the Supreme Court of Justice in the Ionian Islands, and Lear went out to Corfu to join him. Colonel Ormsby was Commanding Officer of Artillery for the Ionian Islands.

[2] Philates was under the control of two powerful local families, one of them headed by Cafer Dem Paşa (Jaffier Pasha). Hospitality was dispensed by his mother, “a celebrated person in her way [who] settles disputes and administers justice in the village. She sits unveiled in her Divan. As a Turk, she eats not with Christians, but keeps a bountiful table” (George de la Poer Beresford, Twelve Sketches in double tinted Lithography of Scenes in Southern Albania, London: Day and Son [1855]).

[3] Sidney Smith Saunders, consul at Prévyza and Signor Damaschinó, British vice-consul at Ioannina; Lear had enjoyed their hospitality on earlier journeys (Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, pp. 337, 342).

[4] This would have been the bridge of Ráiko, strategically placed on the main route from Corfu to Ioannina; Ottoman-era tolls and customs duties levied on roads, passes and bridges, are often mentioned by Western travellers and were much resented by local populations. The fact that the muleteer wanted to avoid the bridge suggests he was working for an inclusive price, as recommended by Murray’s Handbook. Lear’s Albania Journals (pp. 6-7) note that in 1848 he travelled on a fixed daily price to include food, lodging, transport and the guide’s fee; in 1849 he paid a basic one dollar a day, settling up for food, horses, etc. at intervals; the cost worked out roughly the same.

[5] For the Black landlady see Lear's Albanian Journals, p. 18.

[6] In the fourteenth century Sultan Murad I began expanding and consolidating the Ottoman Empire, settling people from the province of Konya (Konyars or Koniároi) in what is now mainland Greece.

[7] Charles Blunt, British consul at Salonica, had helped Lear escape a cholera outbreak in 1848. He later became consul at Smyrna; in his Cretan Journal Lear notes Blunt’s death in Smyrna in 1864.

Editor’s Note

The originals of almost all Lear’s letters to his sister Ann are now lost. Typed transcriptions were made in the 1930s, and my text is based on one of these copies, by kind permission of the present owner, Dr David Michell. The transcriptions were reputedly made with some care and include handwritten corrections and insertions (for instance of Lear’s Greek script) and ink copying of maps and sketches. They nevertheless introduce errors in spelling and, in particular, in proper names. In transcribing what is already a transcription I have tried to be as faithful as possible to Lear’s style as we know it from his autograph letters.

Lear’s punctuation is fairly informal, with copious use of dashes, which I have retained. Ellipsis points indicate where I have omitted material not relevant to the particular journey, and square brackets indicate an editorial interpolation. I have introduced paragraph spacing for ease of reading.

Greek place names are a problem in English but I have aimed to be as clear and consistent as possible. Lear uses accepted English forms (e.g. Corfu, Salonica) where they exist; otherwise he generally follows Leake’s spelling (see W.M. Leake, Travels in Northern Greece, 4 vols., 1835). Many places had two or more different names (Turkish, Albanian, Slav, Greek) until hellenisation became widespread in Greece from the 1920s onwards. I have supplied present-day names where necessary, with stress accents to indicate pronunciation.