Lear in Zakynthos, Ithaca and Cephalonia, 1848

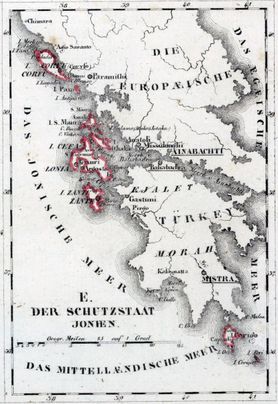

After centuries as part of the Venetian Republic, and briefer spells of French, Russian and Ottoman control, the seven Ionian Islands became a British Protectorate in 1815. Lear first visited Corfu in 1848, and immediately took the opportunity of travelling to three of the other islands: Zakynthos (Zante), Ithaca and Cephalonia. (Shipping timetables frustrated his hope of landing in Santa Maura/ Lefkada, though he glimpsed its coastline from shipboard.) He was to make his winter home in Corfu from 1855 until the end of British rule in 1864. In his later Ionian journey, in 1863, he succeeded in visiting and drawing all the islands.

There are two extant accounts of the 1848 journey: in a letter to his sister Ann (see Editor’s Note) and in the brief introductions to Views in the Seven Ionian Islands, where his livelier early impressions are still sometimes discernible through the more formal prose.

Lear’s lists record that his short visit in 1848 yielded 57 numbered drawings (28 in Zakynthos, 9 in Ithaca and 20 in Cephalonia). These were quick sketches, numbered and with scribbled notes, made on the spot; later, indoors, he would “pen out”, inking over the pencil outlines and adding watercolour or ink wash. The sketches could then be worked up as studio watercolours or more ambitious oil paintings, for exhibition and sale. Lear also returned to the 1848 drawings in preparing his later volume of lithographs, Views in the Seven Ionian Islands (1863), and in choosing scenes for his Tennyson illustrations.

The island landscapes seem a natural fit for Lear’s linear style of draughtsmanship, with their verdant foregrounds and overlapping, succeeding layers of olive or citrus groves and vineyards, with picturesque towns or wide mountains in the mid distance. His Ionian sea is by preference calm and blue. When the earthquake of 12 August 1953 struck the Ionian Islands, Zakynthos, Ithaca and Cephalonia were the worst affected: casualities were heavy and almost all buildings were damaged. Lear’s drawings are therefore part of a lost architectural history.

Zante

Corfù, 14th May, 1848.

My dear Ann,

. . .

So off I set again in an Ionian steamer—starting very early, & arriving at Argostoli (the capital of Cephalonia) at midnight—where we took up Mr Bowen [1]—& at dawn we were at Zante.

Zante, the southernmost of the larger islands is very pretty, & more like one large garden than anything I can compare it to. The town stands by the side of a beautiful bay—& is little more than one or two long streets, while behind, there rises a long, high hill, crowned by the castle. This hill is all split & cracked in a very ugly way—by continual earthquakes, which perpetually occur; & every 20 years the result is very serious: but the intermediate shocks are harmless & nobody minds them a bit—though I must say I should not like to live always in such a neighbourhood. We went to a quiet little inn—not too clean, but just decent. All the towns in the Ionian isles are badly off for lodgings—so few people go there. The city of Zante is by no means composed of fine houses—but very low mediocre dwellings—few higher than one or at most two stories—& often of half wood. The strange feature of the place is that there are no women visible—the old Turko-Venetian custom still prevailing so far as that none of the better class of females go out a bit. Bowen having letters to all the first people, I saw a good deal of the families—& they are very courteous nice people:—all speak Italian except the peasants. There are many palm trees about the town—which look very eastern. The people—higher orders—dress as we do—the lower, all in red caps & Turkey-looking trousers. The red coats of our sentinels & soldiers look odd enough here & there.

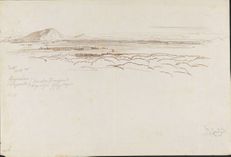

One day I went up Mt Skopo, a high hill at the end of the bay—looking from the top of which a great part of this pretty isle is at your feet like a map. Nothing but a bright green carpet is like it. The carpet is all short grape vine, which produces what we call currants in England, such as you put into “currant dumplings”, & “currant buns”. I declare I always thought those little black “currants” were currants. But they are real grapes, & are part of immense bunches from the little vines, miscalled also currant trees. They came originally from “Corinth”—whence “currant” in course of time. Formerly the wealth of Zante was great owing to the exportation of this fruit, but now it is much less as they grow them at Patras and elsewhere. That part of the island which is not all currants, is olive ground. Some views of the castle hill from the gardens are very pleasing but not striking or grand. Neat little villas, neat little churches—all the roads trim & cut,—everything is pretty & nice in Zante. The city too is respectable after Italian filth. Another day we dined at the country house of Signor Frangopolo, a rich Greek: the dinner was very sumptuous—as good as a London or provincial family would turn out.

The last day of my stay (for, owing to the steamer only touching weekly at the islands, you must stay a week will you, nill you) I went on to the mountain ridge that frames in the west of the island: a pleasant excursion, but productive of no great surprise at the scenery. I visited the 5 convents—& dined at one (San. Georgio), where the long-bearded monks were most venerable-looking fellows. And so much for Zante—a good number of drawings of which I got—but after all it is not very drawable.

Ithaca

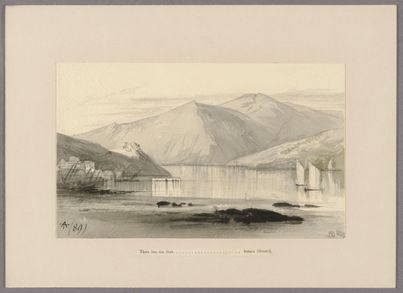

On May 1st, I steamed away to Ithaca—where Bowen left me and returned to Corfù. I got there at dusk, & dined at the officers’ mess 36th regiment. [2]They good-naturedly got me lodgings in a little house, & though I only speak a few words of Greek, yet I manage very well. [3] Next day—2nd—I rose very early, & with Mr Smith, the surgeon of the regiment, & ensign Blund drew & drew & saw a great deal. Ulysses’s kingdom is a little island—& charmingly quiet. I delight in it. The chief town, formed of houses entirely modern, is called Vathi—& it stands at the end of the harbour, so shut in by hills that you would think you were by a lake. In the afternoon we went to the fountain of Arethusa, [4]—& all along the views are quite lovely—of the opposite Greek shore, & of the Ionian isles, Santa Maura, & Cephalonia.

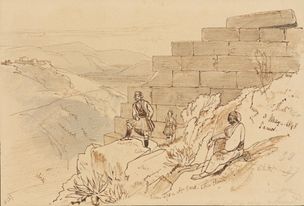

On the 3rd May I proposed going over to Cephalonia, so early, Smith & I went up to the ancient ruins of Ulysses’s city & castle: vast walls of Cyclopean work (like those in the first plate of my Roman book) [5] and sufficient left to attest the truth of the renown of old Ithaca. Coming down at noon, it was very hot, & we found an old hut where there was a great pan of fresh butter milk—but nobody to ask for it—so we drank it up, & put some money in the bowl. I then took leave of my Vathi friends & left Ithaca with the memory of 2 most pleasant days.

Cephalonia

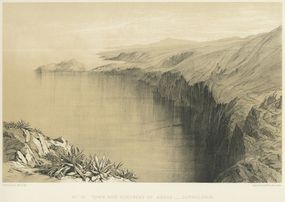

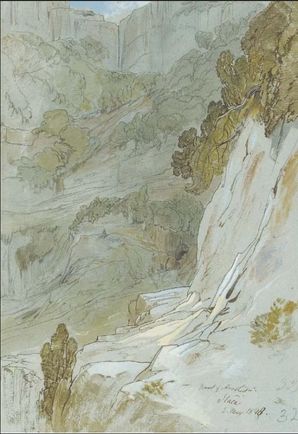

Three hours of a dead calm hardly sufficed to take my ferry boat over to Samos bay—but I wasn’t sick, so I can’t complain. Samos was the greatest of all the cities here about, & that from which the suitors of Penelope came. [6] At present there are not 10 houses—a mere fishery. In one I got a bed, & ordered some supper—going forthwith up to the citadel—the walls of which are magnificent & astonishing, & I am very glad I got there in time to draw them. Next day—4th—I walked over 14 miles & an uninteresting path—to Argostoli—the capital of the island: here is a very decent inn. The city is on a deep harbour, looking like a lake & fronting the grand “Black Mountain”. The houses are better than in any Ionian island city. I found the chaplain very kind, as well as the officers to whom I had letters of introduction: an odd change in my summer life is it not?—that whereas I used to be living scantily in Italian cottages, I am now drinking champagne etc. every day at splendid tables—rather more good living than I like, to tell the truth. The 5th May I passed near Argostoli—visiting fort San Georgio & Metaxata—the last place Lord Byron lived in before he crossed to Greece. The 6th I went to the valley of Racli, in a carriage. There are good roads all over the island of Cephalonia, but the precipices they go close to, without any parapets, are the most frightful I ever saw—considering that the coach wheels are about 3 inches at most from the edge—yet no accident ever happens. 7th Sunday—service at the garrison chapel—very nicely done & pleasing. Afternoon, went over with Capt. Butler to Lixuri, the ancient capital. 8th May—a coach excursion of 20 miles to Asso, a Venetian fort: but the day was very wet, and only gleamy at intervals. Next day, 9th, came the steamer, & although I much wished to see more of the Black Mountain—yet there was still the island of Santa Maura to see, so I left hospitable Cephalonia with a tolerable budget of drawings & very pleasant memories. Alas the steamer did not stop at Santa Maura,—so I have yet to go there,—but it brought me by a slow passage to Corfù once more on the morning of Wed. the 10th.

Explanatory Notes

-

Sir George Bowen, President of the Ionian Academy, a university founded in Corfu in 1824 and closed in 1864.

- The 36th (Herefordshire) regiment of foot, a light artillery regiment, was stationed several times in the Ionian Islands.

- Corfu was Lear’s first encounter with what is now Greece; he was to take lessons and work hard at Modern Greek, becoming fairly proficient in reading, writing and speaking.

- Homer, Odyssey, 13. 405.

-

The walls and gateway of the Pelasgian acropolis of Alatri: a lithographed plate in Lear’s Views in Rome and its Environs (1841).

- Among other places: see Odyssey, 1. 245.

Editor’s Note

Lear’s account is preserved in a letter of 14 May 1848 to his sister Ann. The originals of this correspondence are almost all lost. Typed transcriptions were made in the 1930s, and my text is based on one of these copies, by kind permission of the present owner, Dr David Michell. The transcriptions were reputedly made with some care and include handwritten corrections and insertions. They nevertheless introduce errors in spelling and, in particular, in proper names. In transcribing what is already a transcription I have tried to be as faithful as possible to Lear’s style as we know it from his autograph letters. Lear’s punctuation is fairly informal, with copious use of dashes, which I have retained. Square brackets indicate an explanatory note or editorial interpolation. I have introduced paragraph spacing for ease of reading.

In 1848 Italian place names were still used in the Ionian Islands (to be replaced by Greek forms after unification with the Greek Kingdom in 1864). Zante is therefore present-day Zakynthos, Santa Maura is Lefkada and Cerigo is Kythera. Lear used accepted English forms for Ithaca and Cephalonia.

I should like to thank Stephen Duckworth and Rose Little for their help and advice with this webpage.

![Val di Racli, Cephalonia, [6 May]. Val di Racli, Cephalonia, [6 May].](/____impro/1/onewebmedia/CephaloniaNo.50ValDiRacliHoughton___serialized1.jpg?etag=%22213542-65cc98eb%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fjpeg&ignoreAspectRatio&resize=204,144)